2020 Mobility 21 Southern California Transportation Summit — Generation Transportation

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

By Kat Janowicz

Mobility 21 Leaders Open Up about Equity and Recovery

The board members of Mobility 21 are in the business of moving people and goods. During the group’s 2020 summit, they took leadership to its highest level: They inspired.

It’s important to acknowledge the role that transportation infrastructure plays in perpetuating systemic racism, said Metrolink CEO Stephanie Wiggins. “I’m proud of Mobility 21 for not only acknowledging it, but then stating that we’re committed to transform the way we all do business in transportation to help close the gap of racial inequality and to better serve our communities of color. It says Mobility 21 is not going to be standing on the sidelines.”

Wiggins’ remarks were part of a frank and heartfelt conversation about equity and recovery among some of Southern California’s most influential transportation leaders that wrapped up Mobility 21’s annual conference, held virtually Sept. 17-18. The organization is a powerful coalition of public and private groups dedicated to solving transportation challenges in the seven-county region that makes up Southern California, home to more than 23 million residents.

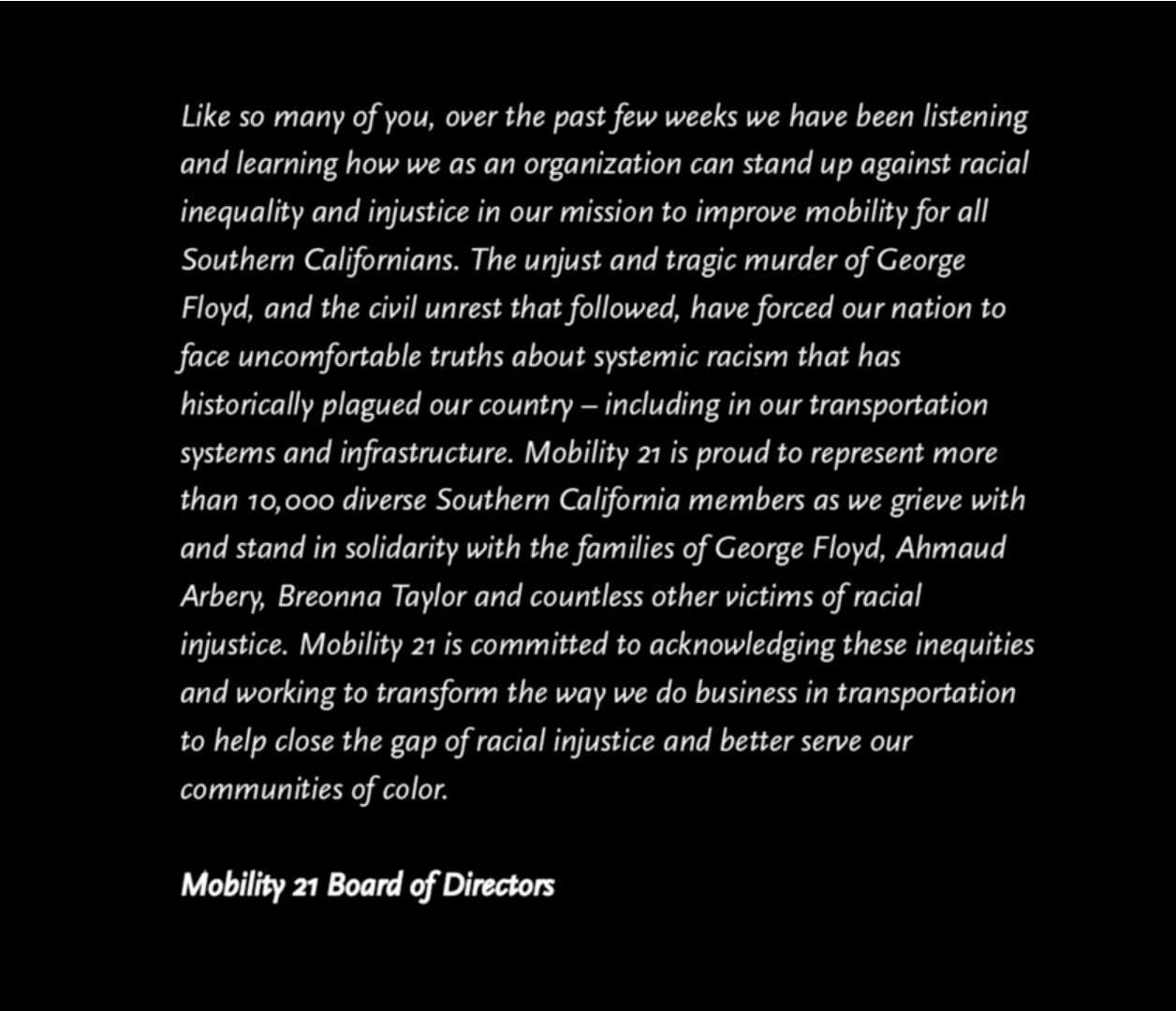

The closing session centered on the Black Lives Matter statement adopted swiftly by Mobility 21 after the death of George Floyd. “The unjust and tragic murder of George Floyd, and the civil unrest that followed, have forced our nation to face uncomfortable truths about systemic racism that has historically plagued our country – including in our transportation systems and infrastructure,” the statement reads, in part.

Mobility 21 Black Lives Matter Statement

“The Mobility 21 statement is emotional, it’s personal, but it’s also really liberating,” said Riverside County Transportation Commission Executive Director Anne Mayer. “We’re using our collective voices to not just talk about what’s important in our profession but to talk about what’s important to us as people.”

“It is sad that we have to make such a statement today, but we must, and we are,” said San Bernardino County Transportation Authority Executive Director Raymond Wolfe. “We can make a difference in the projects and priorities that we advance. Collectively, the leadership on this panel coupled with all our Mobility 21 partners are focused on what is right for Southern California.”

Equity and Recovery

Addressing BLM, issues of equal access to safe transportation, and participation in the planning process was a who’s who of Southern California’s transportation leaders. In addition to Wiggins, Mayer and Wolfe, the panel featured Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) CEO Phillip Washington, Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA) CEO Darrell Johnson, Ventura County Transportation Commission Executive Director Darren Kettle, Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) Executive Director Kome Ajise, San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) Executive Director Hasan Ikhrata, and Imperial Transportation County Commission Executive Director Mark Baza. Seven are on the board of directors of Mobility 21 and two are advisory board members.

During the 90-minute session, the panelists shared their passion for righting the institutional wrongs of racism, social injustice and economic inequity in their industry and the strategies they are pursuing to advance equity in the transportation sector and beyond. They agreed the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately plagued communities of color, has added new urgency to the need to act.

“We shouldn’t be thinking about bridges, we shouldn’t be thinking about buses or trains, we should be thinking about transportation as an essential component to making sure every person has access to these really important things around education, around meaningful employment, around quality health care,” said OCTA CEO Johnson. “It’s more important and more apparent than ever before that we have essential workers that rely on us to get to work to make essential trips. In Orange County, during the worst days of the pandemic, we still had nearly 30,000 people a day riding the bus system … people that had no other choice. This is about people. If we can’t deal with projects and programs and services that serve people, all people, then we’re not doing our job right.”

There’s no denying transportation and other public infrastructure historically favored some and harmed others, said Metro CEO Washington. “Transportation infrastructure has been used to divide communities for so long. Whether it’s highways or parks or whatever. Swimming pools, my God! Black folks can’t swim in the same pool!?”

U.S. Representative, late John Lewis poses for a photo at Black Lives Matter plaza in Washington DC (IG: @clay.banks)

Washington, who grew up on the South Side of Chicago, was among those who told deeply emotional stories about how racism has impacted their own lives. One evening after picking up dinner with his mother and sisters, they drove home only to be surrounded by police when his mother parked the car. Guns drawn, the police were calling him by someone else’s name and shouting at him to get out of the car and down on the ground.

“My mother got out, stepped around to the passenger side between the police and me and said, ‘His name is not Donald Hobson. His name is Phillip Washington.’ Donald Hobson had just robbed a store the night before and they thought I was him. I really believe that they would have killed me that night without asking my name. Had my mother not been there, I probably would have done something stupid like run, and they would have killed me,” said Washington, a U.S. Army veteran who went on to become a nationally recognized transportation leader responsible for running Metro, which serves the nation’s most populated county. Metro is both a transportation planning, design and building agency and a public transit operator with 2,500 buses and eight rail and busway lines serving more than 1.2 million passengers daily, down by half during the pandemic.

“We have made in our industry a very deliberate statement that we will connect communities,’’ he added. He then cautioned “connecting communities” must transcend buzzword status. “We cannot make that a throwaway statement. We cannot make that an irrelevant statement. We’ve got to be real to that statement. To say, wait a minute, this particular project is actually dividing communities, so we’re going to take a stand against it.”

Taking Action

The group agreed that taking a stand means taking action. The panelists discussed steps they are taking now or plan to pursue going forward to make public transportation more accessible to all communities. These include internal operational changes, as well as external strategies, to ensure all communities get the benefit of the vast network of the transit services and projects they manage.

Internal equity measures include:

- Training and messaging to ensure all employees treat all public transit users equally, whether or not they interact directly with the public. This applies to existing services, proposed changes, and future infrastructure projects.

- Implicit bias training for employees from top to bottom.

- Reviewing promotions, salaries and diversity of employees and fixing discrepancies without delay.

- Rethinking how grants and competitive programs are scored and reviewing proposals through an equity lens.

- Ensuring compliance with state and federal equity requirements — not just checking a box — and creating and adhering to additional agency-specific equity policies and processes for assessing programs and projects prior to approval and implementation.

External equity programs include:

- Building job security by making sure people can return to work as soon as possible and investing in communities where transportation is an impediment to people getting back to work.

- Making sure trains are actually serving communities and not just running through them.

- Educating people on the economic benefits of inclusion and how it stimulates the economy.

- Supporting job recovery in the region’s most impacted industries: entertainment, tourism and hospitality.

- Educating people on pricing, how subsidies work and the vast amount of public funding that goes into keeping personal cars on the road compared with public transit.

“We need to make sure that we just don’t continue creating this kind of racial injustice with policies that are softer and kinder and gentler and they seem fuzzier and they seem like they’re really, really progressive, but in fact all they’re doing is still perpetuating the history that got us to where we are today,” said Riverside County’s Mayer.

This includes taking a hard look at existing projects, said San Bernardino County’s Wolfe. “Tragically, I believe we still have a ways to go to truly stamp out systemic racism in transportation. Many of the communities directly impacted by transportation facilities are disadvantaged as we’ve already heard.”

Wolfe cited a proposal by the California High-Speed Rail Authority to locate a new intermodal facility in Colton. “Effectively, what they’re looking at doing is pushing freight into a severely disadvantaged community. The communities in Grand Terrance, Colton, San Bernardino, Rialto and Bloomington are rated by the state’s own CalEnviroScreen in the top 80th percentile of disadvantaged communities. Three of the communities surrounding the proposed intermodal facility in Colton are in the top 95th percentile. So here we have a real-life example of a project that the state of California is advancing that continues the disparity that we are trying to resolve today. We have to do better. We can do better.”

Parochial thinking is another challenge that must be tackled, said Ventura County’s Kettle. “Sadly, that is all too clear in my county where the question of money isn’t a matter of where it should go to make sure we have the best access — it’s ‘That money’s mine and I don’t want it to go someplace else.’ Until we bust down those walls of parochialism in my county and arguably throughout the region, we are not going to be able to provide the level of access that gets economic recovery to those that have really been challenged through the pandemic and our other challenges.”

That’s why changing attitudes begins in-house, said Baza of Imperial County. “What we can do is get the message to our team, our team that is our planning staff, as well as our bus operators all the way down to dispatchers, to make sure they are treating all of our community equally and they understand the benefits of what we are providing our community … that what we do is so important to so many.”

Hastening Change

Among the boldest equity measures is Washington’s proposal to eliminate fares for all Metro bus and train riders. To date, he has created a task force to study the issue, and he plans to bring a proposal to Metro’s board before the end of the year. The strategy reflects what Washington described as the agency’s “moral obligation to pursue a ‘fareless’ system and help our region recover from both a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic and the devastating effects of the lack of affordability in the region,” when he announced the idea in late August.

“Now if that is not equity in the most diverse county in the country with the highest percentage of ridership, I don’t know what is,” he told Mobility 21 conference attendees.

The session was moderated by Rutgers University Professor Charles Brown, an expert in transportation and equity. “What is equity? Equity involves trying to understand and give people what they need to enjoy fuller, healthy lives,” Brown said. “Equity is the presence of justice and fairness within the procedures, the processes and distribution of resources by institutions or systems.”

This is more than just a moment, said SCAG chief Ajise. “This is not going to be a one-year thing. This is going to be a forever thing in our lives. It’s time for wholesale discomfort so we can get comfortable in being bold to do the right thing.”

“Ultimately, it’s about what we can do and what we can enable others to do to fix this systemic issue of racism that we have, the social injustices that we see around us,” Ajise added. “We have an obligation as organizations that are around the issues of dealing with people and helping people to be able to face it head-on and hopefully bring some resolution of some sort in our lifetime so that our children and our grandchildren will not have to deal with this.”

The obligation extends beyond transportation, said SANDAG chief Ikhrata, citing digital access as a key example. Most of our kids are learning online right now and 50% don’t have broadband, he said.

“We have a responsibility as CEOs, not only in transportation … and we should be able to discuss with our colleagues in the public and private sector how we can get equity into all these things. Let us take this seriously to the point where we can do tangible things for the people we serve.”